雅思备考:2023年3月雅思阅读考情分析

阅读量:

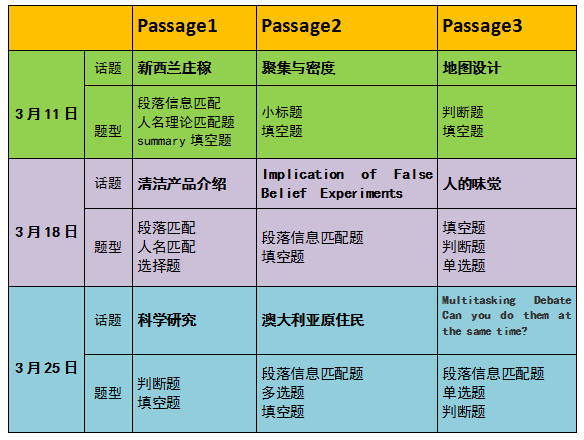

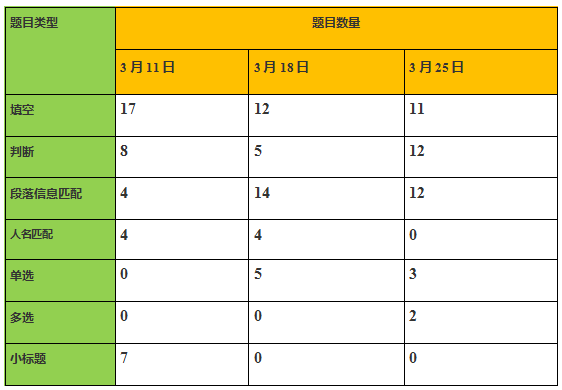

今年3月一共3场雅思纸笔考试,三场考试难度有一定的差异。接下来我们整理了3月所有纸笔考试中阅读文章话题和题型并给出同学们备考建议。

1. 文章话题和题型

2. 各题型占比

3月11日篇文章出现了段落信息匹配题,第二篇出现了标题题,不少同学也反映整体考试难度很大,文章看不太懂;整体其实填空题占比较多,总体难度中等。

3月18日阅读也篇就出现了段落信息匹配题,第二篇也有段落匹配,加上总共出现了五道单选题,对大家的阅读速度是个很大挑战。

3月25日阅读篇是大家最喜欢的判断填空经典组合,难度较低,但是后续两篇文章都是段落匹配题,所以很多同学出现了做不完题目的情况。

3. 备考建议

熟练掌握占比较大的填空题和判断题

熟悉各类题型组合的篇章的解题策略

提高阅读速度

4. 真题信息

3月25 日 Passage 2 题目分析

14-19为段落匹配题

14. B:为了生存而开展的活动【关键词:survival activities,文中提到day-to-day hunting】;

15. A:为了特殊场合而开展的活动【关键词:special occasions,文中提到ceremonies such as initiation】;

16. E:某人以图腾的名字命名【关键词:a person’s name,文中提到be named after】;

17. G: 婚姻模式的变化【关键词:change of marriage,文中说过去一夫多妻制,现在一夫一妻制】;

18. D: 部落的大概数量【关键词:approximate number of tribes】;

19. E: 生物学结果【关键词:biological outcome,文中提到genetic makeup】;

20-21为多选题

20. B:作为某风景特征的代表【关键词:feature of a landscape,文中提到hill, rock等地貌特征】;

21. C: 是一种宗教仪式【关键词:religious ceremony】;

22-26为填空题

22-23暂缺

24. pole

25. 70

26. sick

3月25日 Passage3原文

Multitasking Debate

Can you do them at the same time?

Talking on the phone while driving isn't the only situation where we're worse at multitasking than we might like to think we are. New studies have identified a bottleneck in our brains that some say means we are fundamentally incapable of true multitasking If experimental findings reflect real-world performance, people who think they are multitasking are probably just underperforming in all — or at best, all but one - of their parallel pursuits. Practice might improve your performance, but you will never be as good as when focusing on one task at a time.

The problem, according to Rene Marois, a psychologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, is that there's a sticking point in the brain. To demonstrate this, Marois devised an experiment to locate it. Volunteers watch a screen and when a particular image appears, a red circle, say, they have to press a key with their index finger. Different coloured circles require presses from different fingers. Typical response time is about half a second, and the volunteers quickly reach their peak performance. Then they learn to listen to different recordings and respond by making a specific sound. For instance, when they hear a bird chirp, they have to say “ba”; an electronic sound should elicit a “ko", and so on. Again, no problem. A normal person can do that in about half a second, with almost no effort.

The trouble comes when Marois shows the volunteers an image, and then almost immediately plays them a sound. Now they’re flummoxed. “If you show an image and play a sound at the same time, one task is postponed,” he says. In fact, if the second task is introduced within the half-second or so it takes to process and react to the first, it will simply be delayed until the first one is done. The largest dual-task delays occur when the two tasks are presented simultaneously; delays progressively shorten as the interval between presenting the tasks lengthens.

There are at least three points where we seem to get stuck, says Marois. The first is simply identifying what we're looking at. This can take a few tenths of a second, during which time we are not able to see and recognize a second item. This limitation is known as the "attentional blink":experiments have shown that if you're watching out for a particular event and a second one shows up unexpectedly any time within this crucial window of concentration, it may register in your visual cortex but you will be unable to act upon it. Interestingly, if you don’t expect the first event, you have no trouble responding to the second. What exactly causes the attentional blink is still a matter of debate.

A second limitation is in our short-term visual memory. It’s estimated that we can keep track of about four items at a time, fewer if they are complex. This capacity shortage is thought to explain, in part, our astonishing inability to detect even huge changes in scenes that are otherwise identical, so-called “change blindness”. Show people pairs of near-identical photos - say, aircraft engines in one picture have disappeared in the other - and they will fail to spot the differences. Here again, though, there is disagreement about what the essential limiting factor really is. Does it come down to a dearth of storage capacity, or is it about how much attention a viewer is paying?

But David Meyer, a psychologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, doesn't buy the bottleneck idea. He thinks dual-task interference is just evidence of a strategy used by the brain to prioritize multiple activities. Meyer is known as something of an optimist by his peers. He has written papers with titles like "Virtually perfect time-sharing in dual-task performance: Uncorking the central cognitive bottleneck”. His experiments have shown that with enough practice - at least 2000 tries - some people can execute two tasks simultaneously as competently as if they were doing them one after the other. He suggests that there is a central cognitive processor that coordinates all this and, what's more, he thinks it uses discretion: sometimes it chooses to delay one task while completing another.

Marois agrees that practice can sometimes erase interference effects. He has found that with just 1 hour of practice each day for two weeks, volunteers show a huge improvement at managing both his tasks at once. Where he disagrees with Meyer is in what the brain is doing to achieve this. Marois speculates that practice might give us the chance to find less congested circuits to execute a task — rather like finding trusty back streets to avoid heavy traffic on main roads 一 effectively making our response to the task subconscious. After all, there are plenty of examples of subconscious multitasking that most of us routinely manage: walking and talking, eating and reading, watching TV and folding the laundry.

It probably comes as no surprise that, generally speaking, we get worse at multitasking as we age. According to Art Kramer at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, who studies how aging affects our cognitive abilities, we peak in our 20s. Though the decline is slow through our 30s and on into our 50s, it is there; and after 55, it becomes more precipitous. In one study, he and his colleagues had both young and old participants do a simulated driving task while carrying on a conversation. He found that while young drivers tended to miss background changes, older drivers failed to notice things that were highly relevant. Likewise, older subjects had more trouble paying attention to the more important parts of a scene than young drivers.

It’s not all bad news for those over-55s, though. Kramer also found that older people can benefit from the practice. Not only did they learn to perform better, but brain scans also showed that underlying that improvement was a change in the way their brains become active. While it’s clear that practice can often make a difference, especially as we age, the basic facts remain sobering. "We have this impression of an almighty complex brain/, says Marois, "and yet we have very humbling and crippling limits.” For most of our history, we probably never needed to do more than one thing at a time, he says, and so we haven't evolved to be able to. Perhaps we will in the future, though. We might yet look back one day on people like Debbie and Alun as ancestors of a new breed of true multitaskers.

27-32为段落细节匹配题

27. F

28. I

29. C

30. B

31. E

32. G

34-36为选择题

34. C

35. B

36. A

36-40为判断题

YES

YES

NO

NG

NO